Losing Sleep, Losing Focus: As students get less rest, their cognitive abilities in elements of life start to suffer in performance, enjoyment

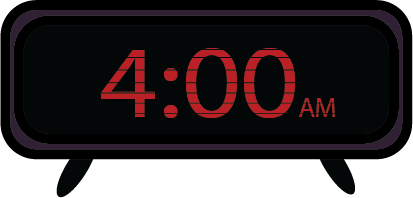

At 4 a.m. each morning, junior Oliver Busenhart stumbles out of bed, often setting over five alarms to finish homework assignments and relieve stress from after-school commitments. Busenhart admits his morning routine appears strange but benefits like lower levels of stress, more energy at school and a positive mindset motivate him to start the day sooner than most individuals.

The American Psychological Association defines a lack of sufficient sleep, less than eight hours, as a rampant problem among teens. Adolescents are at risk for cognitive and emotional difficulties, poor school performance and accidents, as statistics show less teens fail to reach a healthy night of rest.

According to the National Library of Medicine, Biotech Information, sleep benefits the brain by promoting attention, memory and analytical thought. Information and conservations become sharper, intertwining well with learning in a school environment.

With the recommended amount of eight to 10 hours of sleep, rates of creativity grow in teenagers. Tasks like studying for a test, learning an instrument or implementing job skills, sleep is essential for teens in their performance across every spectrum of activities.

Although waking up early can help to ensure all his schoolwork is complete, facilitating less than six hours of sleep impacts his mental health and areas of his personal life.

“I barely manage,” Busenhart said. “I have a lot of things I need to be doing throughout the week and on top of that, there is also home life where I have to get chores done or make dinner for my family. It is a lot to balance out.”

A multitude of factors play into why young adolescents fail to reach the amount of sleep needed to function properly at school, work and after-school commitments.

Senior Margaret Brennan believes too much energy is required of students or rather too little time appears available for each aspect of student life to be fulfilled.

“Teens need the most sleep because we’re growing the most,” Brennan said. “We need to facilitate our minds and bodies, but sometimes it feels like there is no time.”

The first step of Brennan’s morning routine consists of drinking a grape-flavored Celsius. Just like the other 49% of students who reported reliance on energy drinks on a Google survey of 137 responses, Brennan utilizes caffeine to compensate for the negative effects sleep deprivation carries.

“Right by my bed when I wake up, there’s a big canister of Celsius,” Brennan said. “I’ve always been a big fan of caffeine. Celsius is just one aspect of it that I really cling to.”

Junior Emma Masters starts off the day by subsidizing her morning grogginess with a caffeinated beverage. She then drinks a Red Bull toward the end of the day to give her a boost of energy to make it through after-school cheer practice.

“I think that on days when I drink less caffeine I’m completely drained and don’t want to do anything,” Masters said. “My body can’t focus, and I have withdrawal symptoms like jitteriness and headaches.”

Caffeine doesn’t just keep Masters awake during the day, but it takes a toll on her at night, making her incapable of going to bed before 12 a.m. In her attempts to cut back, Masters realizes how deep her dependence on the substance actually is.

In the same survey, 42% of students said they need caffeine to just make it through the day.

“It’s definitely an addiction for a lot of people, and it affects our health because we’re so reliant on it,” Masters said. “It then messes up our sleep schedules, which makes us need it more.”

A high caffeine consumption could pose a threat to maintaining focus during school, and could impact a person’s academic performance over time. But students like sophomore Izzy Hyde and freshman Lura Bracht are not worried their work will be impacted, both feeling grateful caffeine doesn’t have a huge effect on their bodies.

“For me caffeine doesn’t impact my learning, but depending on the person, I could see how it would cause them to get worse grades or have withdrawals,” Hyde said.

Junior Lucy McArthur notices a difference in her overall ability to function at school when her body has too much caffeine running through it. McArthur has since tried to limit her intake of energy drinks and make a conscious effort to drink more water, claiming it gives her a more natural source of energy.

“When I drink an energy drink before school, I’m constantly shaking and get bad headaches,” McArthur said. “It makes me unable to concentrate fully on my schoolwork, which is bad for my grades.”

Only able to attain three to five hours of sleep, senior Caroline Beck, like Brennan, starts her mornings with an energy drink or iced coffee. Despite acknowledging the health risks, Beck failed to fix the root of her lack of sleep due to work responsibilities.

With so much to try to fit into each day, Beck doesn’t allocate sufficient time for sleep. She may stay up late during the week to finish homework or during the weekend when hanging out with friends, both of which can reinforce a night owl schedule

“I work 30 hours a week,” Beck said. “When I get home so late, I hate doing homework. Most of the time, I stay up till 1 a.m.”

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that the less sleep students achieve at night, the lower their grade point average will be. Over 82% of students either agreed or strongly agreed that student performance at school is affected by the amount of sleep they attain.

The Sleep Foundation found the pressure to succeed while simultaneously coping with these activities led to stress, which has been known to contribute to sleeping problems and disorders.

Some teens have poor sleep because of an underlying sleep disorder. Sophomore Katherine McGee’s insomnia diagnosis around sixth grade validated her fragmented sleep and excessive daytime sleepiness.

“I was not at that age where you understand,” McGee said. “It was more of, ‘Why is this happening because all of my friends sleep like eight hours and they are fine and they can keep doing this?’”

With her inability to concentrate in class, the diagnosis forced McGee to quit many of her sports and extracurriculars, which has taken a toll on her mental health.

“I physically could not do it anymore because of the lack of sleep,“ McGee said.

As she has grown with the diagnosis, McGee learned new ways to implement.

Her little sleep is another part of her daily routine. According to McGee, she has learned to accept it as part of her.

“You just slowly grow into not feeling tired,” McGee said. “You wake up a little less tired each day, even though you have got the same amount of sleep or you have got to run off adrenaline.”

In the 20th century, increased usage of screens paired with the marketing of caffeine drinks toward adolescents, has led teenagers who experience inadequate sleep to spend twice as much time on devices with screens than their peers, reported a 2019 study at the University of Minnesota.

Adolescents develop a strong tendency toward being a “night owl,” staying up later at night and sleeping longer into the morning. Experts believe this is a two-fold biological impulse affecting the circadian rhythm and sleep-wake cycle of teens.

Teens’ sleep drives form slowly, meaning feelings of tiredness don’t start until later in the evening. Then the body produces melatonin, which is the hormone that induces sleep.

If allowed to sleep on their own schedule, many teens would get eight hours or more per night, sleeping from 11 p.m. or midnight until 8 a.m. or 9 a.m., but school start times in most school districts force teens to wake up much earlier in the morning. Because of the biological delay in their sleep-wake cycle, many teens simply are not able to fall asleep early enough to attain eight or more hours of sleep and still arrive at school on time.

With reduced sleep on weekdays, teens may try to catch up by sleeping in on the weekend, but this fails to fix the root of the problem.

The implementation of late start days occurring every other Wednesday combats delayed sleep schedules and inconsistent nightly rests. In that same 2019 study, schools that started after 8:30 a.m. had attendance, standardized test scores and academic performance in math, English, science and social studies increase, while tardiness declined.

Beck finds that late-start days offer relief with her busy schedule.

“I love late-starts,” Beck said. “I feel like I have more time to get coffee and make breakfast. I just feel so much better.”

As a student athlete, sophomore Meg Joseph pushes the majority of her energy in the afternoon, making the end of the day difficult. According to Joseph, she arrives home at 6 p.m. after wrestling practice.

“Teenagers definitely expend a lot of energy during school, and it takes a lot of brain power,” Joseph said. “That tends to make people tired and especially student athletes, who not only have to expend a bunch of brain power during the day but also have to go after school and work for two hours.”

This experience of expectations on students to participate in outside activities, work and perform well in school can continue the cycle of inadequate sleep.

“I think that like my work life was interfering with my sleep schedule,” Beck said. “Even my homework was interfering with my sleep too. I just didn’t have time to get everything done. When you wake up early the next day after going to bed late, it just leads to a spiraling moment of always being tired.